Pandemic leads to creation of Napa’s own ‘Court TV’

A year ago, appearing remotely for a Napa court case was a rarity. In some civil cases, parties could call in by phone. For criminal cases, remote appearance options were even more restricted.

Today, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, that’s completely changed.

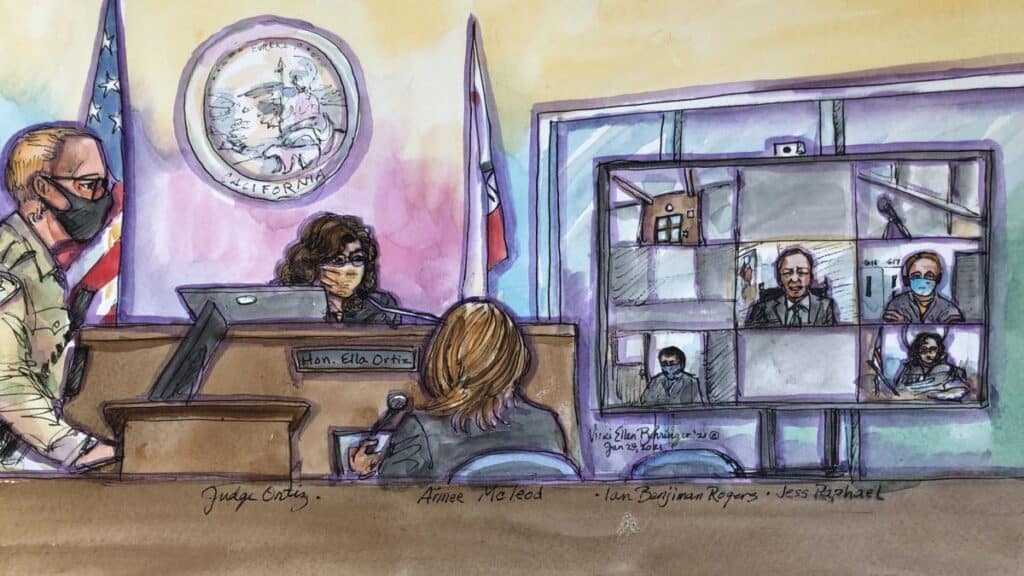

To reduce the number of people in county courtrooms, Zoom access has been added to every Napa courtroom, enabling those involved in cases to appear remotely, whether one or 1,000 miles away.

It also led to something else.

We’re offering our best deal ever with this Editor’s Special. Support local news coverage by subscribing to the Napa Valley Register.

Anyone with a smartphone or laptop can now log in via Zoom and watch real court proceedings in real time. Think of it as Napa’s own version of “Court TV.”

“The challenges of the pandemic were unprecedented,” said Bob Fleshman, CEO of the Superior Court of Napa County. “It came down to access to justice,” he said. “If we didn’t pivot to a digital environment with remote capabilities, we wouldn’t be able to serve the community.”

“I think it’s gone well, overall,” Fleshman said of adding Zoom/remote access to Napa courts.

Napa County Superior Court Judge Scott Young was an early user of Zoom in his courtroom.

“I was really excited for an opportunity to use technology to serve the public and a new way to deal with disputes while keeping the pubic safe and not spreading the virus,” said Young.

In fact, remote video access could remain part of the new normal of the court in post- pandemic times, said Young.

An unintended benefit of the pandemic is that the court system can now provide greater access to those who might have had more of a challenge making an appearance.

Zooming in Napa courtrooms

All nine Napa County courtrooms now have public links to provide Zoom access.

Dozens of cases a day are typically processed in those courtrooms. There are drug, custody, assault, theft, small claims cases, civil lawsuits, family cases and more.

Staffers including bailiffs, judges and court reporters remain on site. Many attorneys seem to be appearing from their offices or homes, but others are in court in person.

Each case is still “called” like normal. The judge begins asking the defendant if they are OK with appearing by Zoom (if they aren’t specifically required to appear in person). Once that is confirmed, the case begins as usual.

Those appearing via Zoom are asked to act as if they were appearing in person, and respect all those present. They are asked to be conscious of what appears in their background as it can be distracting to others. Mute your microphone when not talking, the court requests.

As many as a dozen criminal justice “partners” such as probation officials, the district attorney or public defenders may be on Zoom at the same time. When it comes to more complicated cases, or when a series of defendants are waiting their turn for their case to be heard, that number can reach more than 20.

Anyone can log in, but if asked they must identify themselves. Recording court proceedings without permission is not allowed.

“You can’t enforce it,” admitted Fleshman. To date, “we haven’t had to deal with it yet where someone has illegally recorded” or published such images. “But don’t break the law,” he cautioned.

COVID-19 or not, court proceedings have always been open to the public. Some people make a hobby of watching or observing court cases.

However, “we do not encourage the use of Zoom for passive observance of court hearings,” said Fleshman.

If too many “lookie-loos” try to watch on Zoom at once, “it would muddle the experience for those actually appearing in court remotely, not to mention the ‘crowd management’ challenges that would fall to the courtroom clerk who is documenting official court actions in each case.”

“This is why we haven’t marketed Zoom for mass consumption,” he said. Instead, the court prefers that spectators listen via audio, not via Zoom.

A glimpse into Napans’ lives

Watching court hearings via Zoom provides an unexpected and personal glimpse into the lives of those involved.

Defendants are seen logging into Zoom from inside vehicles, on couches, front porches, at kitchen tables, conference rooms, jail, Napa State Hospital and even hospital beds.

They sip from coffee cups and soda cans. They pet dogs or talk to someone off-camera. Some forget to mute their microphones. Some can’t figure out how to turn on their microphones. Some don’t show up.

Each is like a chapter in a story.

A mother asks for more child support to pay her son’s daycare provider. The boy’s father is told he has two weeks to get a job, any job.

A woman’s attorney claims she was not speeding down Lincoln Avenue this past November; the officer’s radar gun might not have been working correctly. The judge disagrees. She is ordered to pay a hefty fine and attend traffic school.

A recently arrested man asks for his bail to be lowered. A judge does not agree. The man will remain in Napa’s jail.

A drug court participant happily reports his successful progress. Supporters seated around him applaud.

A couple wants a caterer to return their down payment from a wedding dinner that didn’t happen as planned. The caterer disagrees. Plus, he doesn’t have the money.

A man claims he takes cannabis for back pain. The judge asks him to submit a doctor’s note.

When asked, a judge gives a defendant who has a young son about to celebrate a birthday a few extra days to turn herself into jail.

Another defendant doesn’t appear when his name is called. After waiting to make sure he’s not on Zoom, a bench warrant is issued for his arrest.

A resident of Napa State Hospital cries while the attorneys and the judge talk. She’s distraught.

Some defendants talk when they’re not supposed to. Others listen quietly and only give minimum answers.

Others look confused and don’t seem to understand the legalese being tossed around. Judges and attorneys pause to clarify.

Some defendants explain their circumstances and positions succinctly. Others ramble or aren’t able to respond effectively. Those Zooming from hospital beds look particularly vulnerable.

Judge Young said he is mindful that the people who come into the courtroom or criminal justice system are going through significant life experiences.

That includes victims who want their story to be heard, witnesses who may be scared to be testifying in court, and even the accused who oftentimes might have mental health, addiction or other significant issues, said Young.

For victims who need access to a computer to log into Zoom, a workstation is available at the Family Justice Center within the Aldea Children & Family Service building in downtown Napa.

Yuen Y. Chiang, victim services manager with the Napa County District Attorney’s Office, said being able to testify or participate in court via Zoom is particularly beneficial for victims.

“A lot of people are afraid to go to court” for a variety of reasons, she said, including immigration status or fear of retaliation.

Most feel much more comfortable appearing remotely than in person, she said. Appearing via Zoom is much more convenient for those with less flexible work schedules or child care needs, Chiang added.

The ability to appear remotely via Zoom “has taken out a lot of the anxiety,” of testifying, said Chiang. “It’s just more private.”